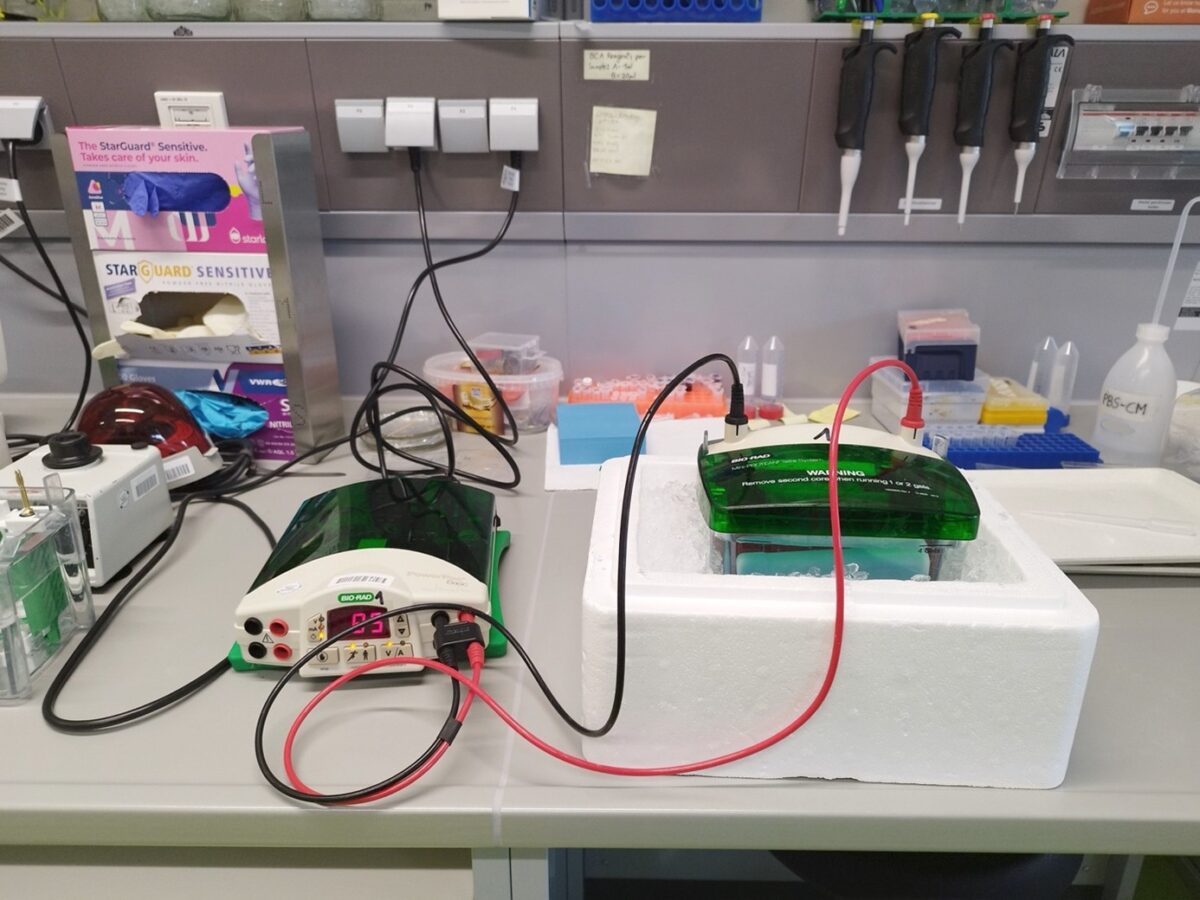

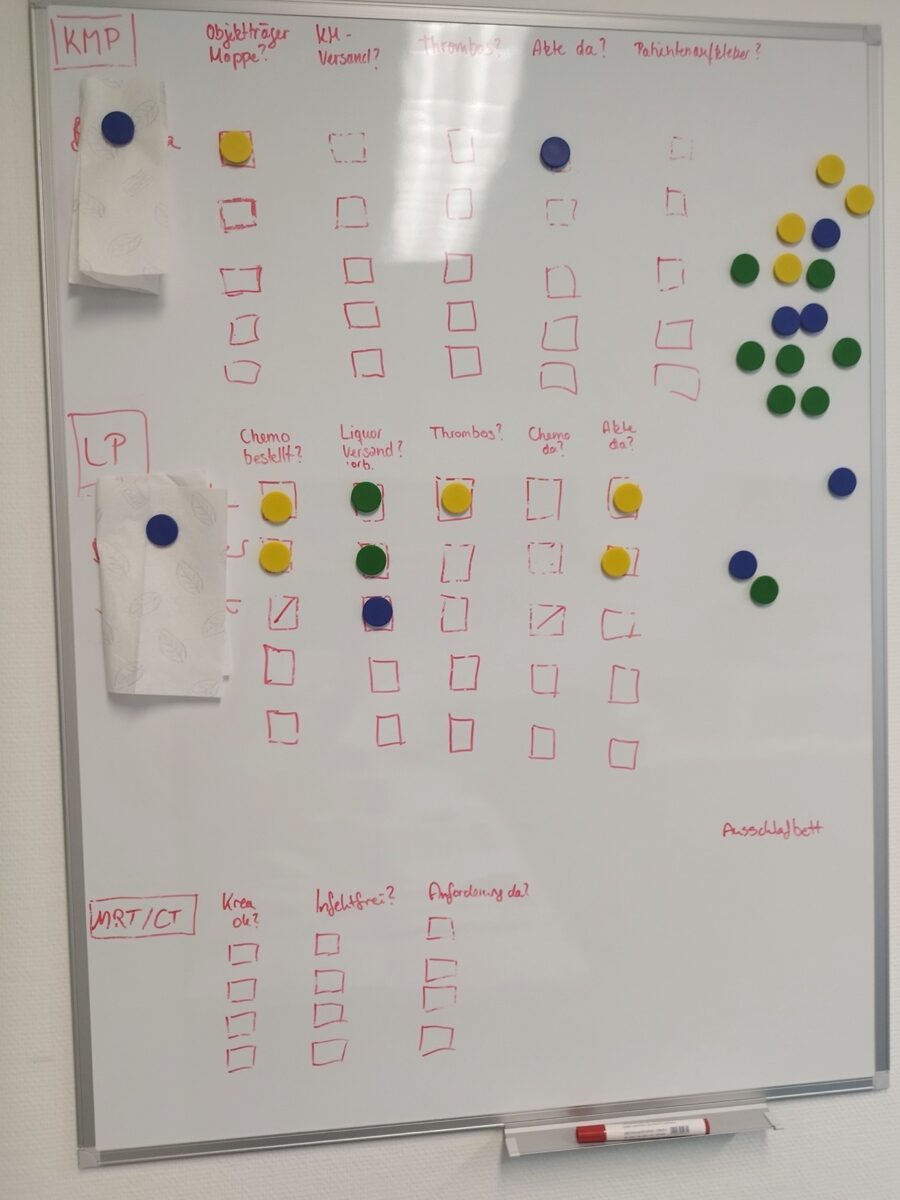

Figure 1: The ‘boring’ infrastructure of desk work that is part of conducting ethnographic research. Goethe University Frankfurt. Picture taken by author, October 6, 2025.

By Timo Roßmann

There is a useful device in my office: a see‑through partitioning wall, installed during the onset of COVID‑19. Once meant to block viral exchange in this shared office, it now serves as a surface for sticky notes. On one of them, I wrote down a brief quote.

“If research systems become too rigid, they turn into devices for testing, into standardized kits, into procedures for making replicas. They lose their function as machines for making the future.”

(Rheinberger 1997: 80)

My PhD research focuses on scientists and health care professionals who study, diagnose, or treat rare conditions. As an associated member of the RTG Fixing Futures, I am interested in biomedical practice and how engaging with rare conditions can challenge ideas of what constitutes reliable knowledge production. I conduct three ethnographic case studies at 1) a biology lab that bases its experimental materials on a rare condition to study cellular disease mechanisms, 2) a medical center offering guidance and tentative diagnoses to patients who are suspected of having rare diseases, and 3) a pediatric unit treating young patients with rare oncological and hematological conditions. In these lab spaces, offices, and hospital wards — all part of academic institutions — I examine how cooperative practices influence knowledge exchange, the epistemic strategies and technical devices employed to manage uncertainty, and the negotiation of evidentiary standards. One of my goals is to develop an understanding of the infrastructural politics that underlie these types of biomedical work and probe whether collaborative practices in rare‑disease contexts challenge, adapt, or reinforce frequentist rationales. Such rationales include the pervasive belief that observing controlled phenomena more often improves knowledge of disease (Zuiderent-Jerak 2021, Bowker and Star 1999). Understanding how practices are mediated and what rationales underpin them allows me to sketch out how these professionals are anticipating and shaping the future of biomedical care for people with rare diseases, and whether their practices reinforce existing biomedical evidence hierarchies or push them in new directions.

In his book Toward a History of Epistemic Things, Hans Jörg Rheinberger engages with the work of Paul Zamecnik’s research group at Harvard University, tracing the development of the first in-vitro system for protein biosynthesis and its central role in the emergence of molecular biology. Focusing on the technical-material configurations of laboratory work (including “experimental systems”), he shows how objects that are not yet fully understood (“epistemic things”) emerge as drivers of scientific inquiry and embodiments of innovation. In the quote above, he suggests that once experimental systems solidify, they cease to produce new structures of inquiry and instead test, replicate, stabilize—or ‘fix’—knowledge systems.

Rheinberger’s claim appeals to me because it suggests that scientific infrastructures, once established, become recalcitrant to transformation. Conversely, my irritation with Rheinberger’s claim is based on observations made during fieldwork—particularly regarding aspirations of professionals to mobilize biomedical infrastructures to accommodate the management of rare diseases. When medical or advocacy professionals described what was needed to shape a future in which rare conditions are better understood and patients better served, they emphasized devices that stabilize knowledge: standards, protocols, guidelines, and nomenclatures that make practice dependable and comparable across time and place.

My inquiry into the future of biomedical practice rests on ruminations about such ‘devices.’ I understand knowledge devices to have both epistemological and ontological character—they are tied to specific styles of reasoning (Hacking 1990) and create new relations that make up the world (Mol 2002). I concur with Andrea Ballestero and Yesmar Oyarzun (2022), who write that “devices are technical, artificial, and eminently cultural objects that shape the very grounds on which we organize sociality” (ibid.: 232).

Especially Ballestero’s (2019) discussion of “techno‑legal devices”—forms, indexes, pacts, and the like—shows how artifacts can fuse technical, legal, and moral work to perform and stabilize political distinctions and future possibilities.

Simultaneously, Ballestero and Oyarzun (2022) conceptualize the ‘device’ as a feminist ethnographic tool: engaging with devices can bring about “[a] difference that makes a difference” (ibid.: 229)— one that sets a new course—and create entry points for contesting “legacies of oppression and exclusion” (ibid.: 228). Tomás Sánchez Criado and Adolfo Estalella (2018) make a complementary methodological claim: by newly ‘devicing’ ethnography—experimenting with ethnographic devices—researchers can foster epistemic partnerships with actors in the field. Treating ethnography as inherently collaborative, Criado and Estalella distinguish three modes of cooperation between ethnographers and their partners in the field: transactional exchanges, sharing political aims, and experimental collaborations.

I put these ideas into practice across my cases, experimenting with varied modes of ‘devicing’ ethnography to complement participant observation, interviews, and document collection. The head of the biology lab and I agreed that patients and their families hold extensive knowledge—not only about living with disease but about the bodily processes involved. Together, we co‑designed patient–scientist workshops in which the head of the lab mapped known organismal phenotypes and their links to cellular dysfunction, while patients and family members were invited to contribute insights from lived experience and identify underexplored research avenues. While I envisioned the workshops to be instructive, they felt cumbersome for both researchers and patient families. They favored a transactional form of exchange, where patient families sought updates on ongoing projects from the researchers and were eager to contribute to the advancement of their projects, and biologists used the contact with patients as a motivational source, to collect urine samples for research, and to practice community outreach.

At the medical center which reviews patients’ medical files to propose provisional diagnoses, I assisted with organizing lists of affiliated treatment centers and drafting standardized forms. I intended this work to surface how my interlocutors and I conceptualize such “boundary objects” (Star and Griesemer 1989) and to engage practitioners in reflection on the epistemic roles these devices play. In practice, however, my efforts were subordinate and geared towards service to the medical discipline (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys 2008). I produced tools that facilitated medical work without provoking reflection on the knowledge relations they instantiate. I came closer to what seemed like both a collaborative and interventionist frame during a nearly two‑hour interview with a patient whose case the center was processing.

At the patient’s request, I shared the interview audio with the patient’s general practitioner, who reported that details from the interview strengthened his suspicion that the patient’s condition involved the central nervous system. In this instance, a shared ethnographic device—an interview—fed into clinically actionable insight and potentially made a difference in the patient’s diagnostic trajectory.

Subordination-service mode (ibid.), however, also characterized my efforts to move beyond observation in the pediatric oncology and hematology unit. In interdisciplinary case discussions—bringing together medical, nursing, and psychosocial teams—I was sometimes asked about families with whom I had built rapport, folding me into the expectations directed at psychosocial staff: that non‑medical professionals manage everything beyond the narrow scope of medical treatment and thereby help render patients ‘treatable.’ Such moments clarified institutional divisions of labor and the limits of what different professionals can legitimately do, but they also flagged the moral economies that shape collaborative expectations.

Pushing up against those limits was tedious, but doing so sharpened the ethnography’s ability to show when and how distinct registers of knowledge become productive. The most resonant engagements between my interlocutors—both professionals and patients—and myself centered on a more mundane device: the case. The biologists attended to single cases when they monitored experimental effects on individual biological replicates. Medical staff organized around single cases needing resolution. Clinicians in pediatric oncology and hematology relied on compilations—charts, histories, imaging, and lab results—that, together with the patient’s body, constitute a case. Moreover, the patients’ families trustingly told me about what they conceived to be ‘their cases.’

Cases operate across scales: as diagnostic objects, pedagogic tools, and devices for generating and comparing knowledges (Mol 2023). Martha Lampland and Leigh Star’s (2009) invitation to attend to the “boring” devices that make up scientific infrastructures resonates here: many tools, schemes, and strategies in science are designed to support work and facilitate empirical engagement without continuous attention to them (ibid.: 11; see also Griesemer 2016: 210). The ‘case,’ then, is a device that continues to occupy a central position in biomedical practice and ethnographic inquiry (Morgan 2020: 212).

Although clinicians prioritized reproducibility and guideline-based quantitative evidence when treating rare pediatric cancers, they resorted to case studies for the rare among already rare cases—patients who did not tolerate protocolized treatment or showed unexpected reactions. Studying single cases ranks low in formal evidence hierarchies (Wieringa et al. 2018), but in practice, ‘thinking with cases’ can have considerable effects: cases focus attention, structure collaboration, and enable reasoning when calculative devices—deeply entwined with the cost–benefit analyses that justify public health spending (Amelang and Bauer 2019)—reach their limits.

Coming back to Rheinberger: Both randomized controlled trials and case studies are established research systems within biomedicine, but they are devices with very different future-making capacities. Preeminence of the former reinforces existing practices, categories, and hierarchies—reifying the status quo of biomedical practice— and increased focus on the latter may open biomedical practice to transformation (Wieringa et al. 2018). That is why I would like to respond to Rheinberger’s claim with a humbler proposal. I suggest that standard-setting devices should be considered transformative indeed, because standardization redistributes epistemic authority: determining which phenomena count, which measurements are valid, which accounts are privileged, and who participates in producing them. By tracing how devices are used, contested, and reworked in collaborative settings, ethnographers can make visible the infrastructural politics that will shape biomedical futures.

Practically, this means attending to the ordinary materials that organize work—standard operating procedures, protocols, forms, checklists, or case files—and treating them as analytic entry points. It also means experimenting with ethnographic devices in ways that foreground shared problem framing and utility for those with whom we share aspirations for the future (Ballestero and Winthereik 2021). In this sense, thinking with devices that standardize practice has not lost its political salience—and certainly not its function as a machine for making the future.

References

Amelang, K. and Bauer, S. (2019) “Following the Algorithm: How Epidemiological Risk-Scores Do Accountability,” Social Studies of Science, 49(4): 476–502.

Ballestero, A. (2019) A Future History of Water. Durham: Duke University Press.

Ballestero, A. and Oyarzun, Y. (2022) “Devices: A Location for Feminist Analytics and Praxis,” Feminist Anthropology, 3(2): 227–233.

Ballestero, A. and Winthereik, B.R. (eds.) (2021) Experimenting with Ethnography: A Companion to Analysis. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

Barry, A., Born, G. and Weszkalnys, G. (2008) “Logics of Interdisciplinarity,” Economy and Society, 37(1): 20–49.

Bowker, G.C. and Star, S.L. (1999) Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press.

Griesemer, J.R. (2016) “Sharing Spaces, Crossing Boundaries,” in G.C. Bowker et al. (eds.) Boundary Objects and Beyond. Working with Leigh Star. Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press. 201–218.

Hacking, I. (1990) The Taming of Chance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lampland, M. and Star, S.L. (2009) “Reckoning with Standards,” in Standards and Their Stories: How Quantifying, Classifying, and Formalizing Practices Shape Everyday Life. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. 3–24.

Mol, A. (2002) The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

Mol, A. (2023) “Exemplary: The Case of the Farmer and the Turpentine,” in E. Yates-Doerr and C. Labuski (eds.) The Ethnographic Case. Manchester: Mattering Press. 43–46.

Morgan, M.S. (2020) “‘If p? Then What?’ Thinking Within, With, and From Cases,” History of the Human Sciences, 33(3–4): 198–217.

Rheinberger, H.-J. (1997) Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Sánchez Criado, T. and Estalella, A. (2018) “Experimental Collaborations,” in A. Estalella and T. Sánchez Criado (eds.) Experimental Collaborations. Ethnography Through Fieldwork Devices. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books. 1–30.

Star, S.L. and Griesemer, J.R. (1989) “Institutional Ecology, `Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39,” Social Studies of Science, 19(3): 387–420.

Wieringa, S. et al. (2018) “Different Knowledge, Different Styles of Reasoning: A Challenge for Guideline Development,” BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 23(3): 87–91.

Zuiderent-Jerak, T. (2021) “STS as a Third Space between Evidence-Based Medicine and the Human Sciences,” in G.L. Downey and T. Zuiderent-Jerak (eds.) Making & Doing: Activating STS Through Knowledge Expression and Travel. Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press. 197–218.